Whether it’s broccoli in the teeth, frosting on the chin, a shirt inside-out, it often takes someone else – with honesty and caring – to help us notice what we haven’t yet seen for ourselves.

As we dig deeper and deeper into the wide body of research that shows us how children learn to read, we have become more and more aware of a mental model that has actually made learning to read harder, rather than easier, for many children.

You may be wondering, “What’s a mental model, anyway?”

In this context, the term mental model refers to the internalized structure, or framework, that drives our unconscious decision-making. For example, you probably have a mental model for classroom management. That mental model was formed early in your practice when you had to think through every management move you made with students.

Now, however, if you have a few teaching years under your belt, many of your behavior management moves are done without thinking. You have internalized a mental model for how to manage students–informed by what you believe is important in the classroom and what kind of relationships you want with students.

If you established a mental model that classrooms should be quiet places, then your now-unconscious management moves will reinforce that. If you believe there should be a productive hum in the classroom, then the automatic moves you habituated around this mental model will make space for student chatter.

This all matters because once your mental model is established, it becomes almost invisible to you. It’s just become a part of who you are and how you do business. But habituated moves can make it harder to see the WHY behind what you are doing because your instructional moves aren’t conscious.

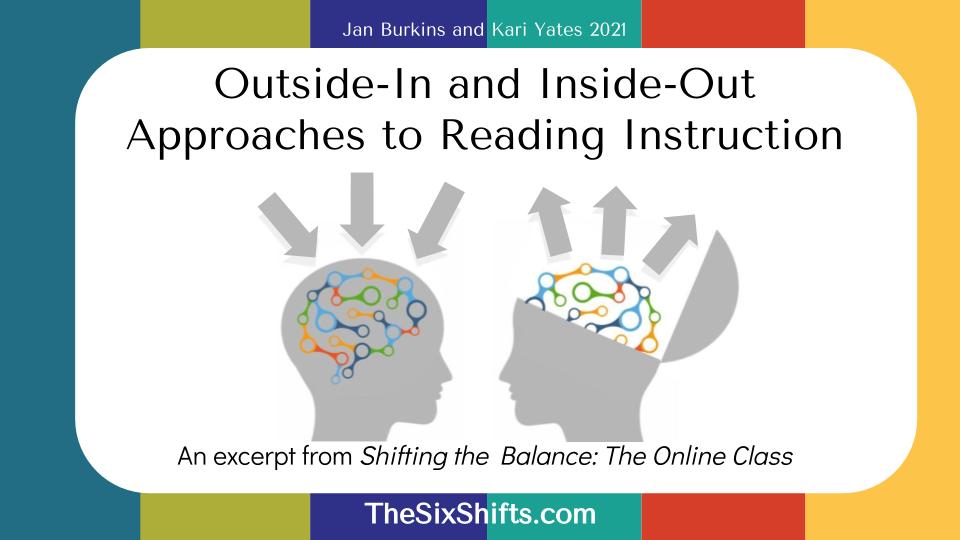

When it comes to reading instruction, the mental model that informs many of our core practices in the balanced literacy classroom is an “outside-in” model (Adams, 2000). That is, it is based on assumptions developed from watching–from the outside–as children read, and then inferring what is going on inside their brains. This seems perfectly logical, except that, as it turns out, a lot of what goes on inside the reading brain is not so obvious from the outside. We first learned this outside-in/inside-out idea from Marilyn Adams, in her insightful book, Beginning to Read: Thinking and Learning About Print.

As it turns out, our intuition is not enough to make learning to read easier for kids. We need some science.

The alternative mental model is based on what cognitive research shows us about how children’s brains actually read. This “inside-out” model is actually counterintuitive sometimes. But shifting your mental model to one that follows the lead of the reading brain can make learning to read dramatically easier for your students.

For example, from an outside-in perspective, it seems like children use context to figure out words. But what we know about the brains of proficient readers is that they always decode words first and then use context to confirm. Understanding this linear brain process vs. the intuitive, outside-in “searching for sources of information” process, can profoundly increase the success of your students, especially as they begin to read more complex texts.

Basically, some of what we have assumed is going on inside children’s brains as they learn to read just isn’t accurate.

You can scrutinize your mental model for how you teach reading (or how you do anything) by interrupting your habituated practices and asking yourself, “Why am I doing this?” Somewhere down the line, you adopted that practice because you believed something about how children learn to read. Many of those practices will hold up when you examine them. But some may be based on mental models that need revision.

If you want to learn more about outside-in vs. inside-out models for reading instruction, including the WHY and the HOW of revising some less-effective, outside-in practices, we invite you to join us for our next round of Shifting the Balance: The Online Class.

Reading Shifting the Balance was revolutionary! I used the book study guide, bought a set, and used it with my teachers. We are currently “Shifting the Balance” in Texas and training all K-3 teachers in the Science of Teaching Reading. As a cohort leader, it has really helped my teachers see how it all comes together, especially when we have been heavy on the reading recovery side of the spectrum for so long. Thank you for your research and work!

April,

We’re so excited to hear that Shifting the Balance has been a helpful tool in helping teachers in your district see how things “come together”. Our ultimate goal is to make learning to read easier for children. We wish the best on your learning and leadership journey!

Jan and Kari