We all know that teachers, not programs, make the difference when it comes to effective instruction. Scientific research bears out this idea that teachers matter more than programs, especially when it comes to beginning reading (Bond 1966; Readence & Barone 1997). But, in our years in classrooms across the country, we have also seen the difference that access to high-quality curricula can make in the lives of hard-working teachers and the children they serve.

And, as seems to be the case with most aspects of life, there is some “good” news and there is some “bad” news when it comes to literacy programs.

Understanding Curriculum Evaluation:

“The GOOD” and “the BAD” of Programs

Good news: There are some really good programs out there, and, more and more, publishers are making materials that are beautiful, sound, and engaging. But even the strongest programs will need to be looked at critically, considering how they do or don’t meet your particular needs. So, you will need to know exactly what you are looking for and what your priorities are before you begin the selection process.

Bad news: Perfect programs simply don’t exist. This is not a surprise! Even with a program that you love and have relied on for years, there are probably at least a few things that you would like to tweak. The trick is finding resources that need the least adjustment to begin with.

Good news: When you put in the time to identify your local priorities, you’ll be equipped to weave together a sound combination of programs and professional development. You will also be less likely to fall for the bells and whistles that can distract you from really looking closely at the more critical elements of a program.

Bad news: The complexity of resource selection means that nobody outside of your school or district can decide exactly which program is right for you. Factors such as the history of your materials adoption in the school, previous professional development, other resources already on hand, budget restraints, and more will all interplay in unique ways.

Good news: You have a lot of options. You can choose something that is comprehensive or something more specific to an aspect of your literacy instruction, such as phonics or high-frequency words. The trade-off for specificity, of course, is that selecting a program for particular components may require extra planning to coordinate and connect them. And the drawback of a more comprehensive program is that it is sure to have gaps and extra components that you don’t need or don’t have time for. For example, one program might be really strong when it comes to knowledge-building but provide spotty attention to word recognition, while another program offers just the opposite. Whether you decide to skillfully weave a few options together or invest in something locally developed to fill in the gaps, there will be a lot for you to think about.

Bad news: Finding a strong program doesn’t mean you’ll automatically have strong instruction. As we already mentioned (and you already know), teachers are the real difference-makers. Programs are just resources that school leaders must pair with ongoing professional development and teacher support.

So, what is a literacy framework, and why does it matter?

The real work of finding the right programmatic materials for your school or district begins long before you google “best reading curriculum,” visit a conference vendor booth, or invite a sales rep in for a presentation. The work begins by designing (or refining) your local literacy framework.

A literacy framework is a thoughtfully designed structure that represents your literacy instruction. The framework serves as a roadmap for teaching literacy across the grades—communicating school or district values and priorities; highlighting local strengths, needs, and opportunities; and framing a shared understanding of effective and science-aligned instructional “must-haves.” Though ideally simple in design, the supporting documents of a literacy framework serve as a guide for decision-making and transparent communication.

With each team bringing its own ideas for content, conceptualization, and presentation, literacy frameworks are as unique as the leadership teams that design them. However, this doesn’t mean that a literacy framework is just a compilation of everyone’s favorite teaching moves or a reflection of beliefs that aren’t backed by research. Rather, common threads run through any science-aligned framework, such as a commitment to a shared scope and sequence, priorities for the types of texts that students read, and guidelines for how instructional time will be spent in the literacy classroom.

Because a literacy framework should be constructed before a team starts looking at specific curricula, the framework can actually serve as your guide when evaluating programs and selecting the resources most suited to help you achieve your identified priorities.

During the selection process, the literacy framework also safeguards you from ambiguous labels, shiny boxes, and over-reliance on the expertise of program-specific representatives. Most of all, it can keep your team grounded so that you don’t end up with a program that consumes your time, dictates your instruction, and depletes your financial resources. A framework will help you

select programs that really do meet the instructional needs of students and the professional development needs of teachers.

What are some considerations for developing a literacy framework?

So, how do you design a science-aligned and responsive framework that a whole school understands and can get behind? Well, it takes time, effort, and committed leadership. Generally speaking, the process often hinges on three critical steps:

1. Form a literacy leadership team. Effective leadership for literacy is not achieved by a single person, such as the building principal or a literacy coach. Constructing a solid framework will hinge on the collaborative efforts of a committed team that includes the expertise of a wide range of local stakeholders such as classroom teachers, special education teachers, school psychologists, speech clinicians, interventionists, instructional coaches, and more.

2. Take a close look at the research. Today, more than ever, it’s critical to turn to reading research for accurate answers to critical questions. To help your team look for patterns in the research rather than rely on individual studies, which are often contradictory, we created this simple guide to understanding reading research.

Based on your school or district’s strengths, needs, and opportunities, you will have to decide which components of literacy instruction are most important for you, whether language development, phonemic awareness, phonics, comprehension, or more. Then, you will want to find out what the research really says about science-aligned instruction in each of these areas. This investigative work will take some time and some effort.

The Shifting the Balance Books and classes can serve as a shortcut for this research work. Each chapter summarizes the key research in an essential area of literacy instruction and describes some high-leverage teaching moves for translating that research into classroom practice. Niki, an instructional coach in Sioux City, Iowa, explains,

Currently, our district is going through a literacy curriculum adoption. As you know, looking at curricula can be overwhelming—there are so many pieces—lesson formats, routines, scope and sequence, student texts, professional learning for teachers, etc. One doesn’t know where to look and focus one’s attention. However, this course provided a lens on which to place my attention. For each shift, I dug into the curriculum materials to see how they aligned with the new learning I was acquiring with this course. I know this will be invaluable in my role as an instructional coach when I support teachers as they make instructional shifts in their classrooms with new literacy resources.

You can learn more about our online class options here.

3. Take stock of current practices and resources. The work of the literacy leadership team goes far beyond choosing materials. After equipping yourself with an understanding of the research, it will be time to take stock of current practices and resources. To support your team in approaching this work with open hearts and open minds, you may want to share our 6 Commitments with them. We wrote it to support teams with the vulnerable work of identifying the absence or presence of practices that may prevent students from experiencing a coherent, cohesive, and brain-friendly plan for literacy instruction across the grades. Of course, this work isn’t only about identifying gaps and overlaps. You’ll also want to be sure to identify instructional pieces that are already strong in your school or district so you can intentionally hold onto them. This will help you avoid pendulum swings and over-correction. And, because it can be hard to see the obvious if it is part of an accepted norm, an outside perspective is often helpful.

You’ve identified your needs. Now start exploring!

We know you have a vision for instruction that is both brain-friendly and kid-friendly, so next, you’ll look for resources that are teacher-friendly. The materials you choose will need to support consistency and make space for flexibility across classrooms while aligning with the research you’ve studied and the priorities you’ve set.

If you decide that purchasing a program (or programs) is the right route for you, you’ll still have some homework to do before you start to unpack sample boxes and get excited about one set of bells and whistles over another. Here are some steps to consider.

- Identify curricular “Must Haves” and “Look Fors.” Once you’ve identified your needs, you’ll be ready to make a short checklist or rubric of “MUST HAVES.” These are features or components that, if not present in the curricula, are deal breakers. You’ll also want a list of “LOOK FORS”—features or components that are ideal but not required, often because you know how to compensate for their absence.It can be helpful to choose a guiding lens as you work through materials. There are several choices for a holistic perspective to guide your review of curricula. Here are just a few examples; you can choose all that are important to you.

- Purpose: What is the specific purpose of this particular curriculum? Is it comprehensive, addressing everything from core instruction to interventions? Or is it specific to a particular aspect of learning to read, such as phonemic awareness? Do the program’s priorities align with your priorities?

- Research: What are the theoretical underpinnings? Who wrote the program? In what ways will it meet your need to support language comprehension and the word reading required for reading proficiency?

- Standards: How well does it align with relevant curricular standards? Is the alignment deep and meaningful, or do the materials just pay lip service to critical grade-level standards?

- Bias and Representation: Do the authors of the materials hold beliefs and priorities that represent the beliefs and priorities of your school and district? Will the students in your school see themselves represented in the materials in positive and affirming ways?

- Time: How much time is required to implement the curriculum? Is it realistic in terms of the instructional schedule? If not, could the materials be modified without compromising the integrity of the program?

- Cumulative Logic: Is the program built on a logical scope and sequence? Do lessons build on one another—from simple to more complex—in logical ways?

- Engagement: Are the lessons and the materials that support them likely to engage students? How do you know?

- Assessment: How time- and labor-intensive is assessment administration for this program? Are the assessments reliable measures of the related learning? How do you know? What biases might make the assessments less valid, i.e., representations, format, theoretical underpinnings, etc.? How well will the assessments inform a teacher’s next steps for instruction?

- Take the materials out for a test drive. Before going all in with a particular curriculum, consider engaging in a “test drive” of the program. Test drives are often most effective when the same group of people within a school or district sample a handful of lessons or units from more than one resource rather than different educators, teams, or schools piloting different materials. Often, once you’ve invested in trying out a particular product, it’s easy to start to appreciate it and think it’s “the one.” especially if it’s the only one you’ve tried. This bias toward familiarity can actually complicate decision-making rather than inform it. So, enlisting a few teachers to “test-drive” more than one program can give them all points for conversation and comparison.

- Plan for ongoing professional development. Most purchased curricula come with options to access or purchase initial professional development that offers program-specific orientation and guidance. However, bringing your literacy framework to life in classrooms will require intentional and ongoing professional development, not only on program-specific routines and resources but also on high-leverage instructional moves and routines that transcend any specific program.

- Build momentum through clear communication. So you have a vision, and you’ve found materials to support teachers in enacting that vision in the classroom. Now the work shifts to communication—-carefully planned, ongoing, clear communication. Educators will need to understand how the resource was selected, the “why” (the research) behind its features and routines, and how they will be supported in implementing it.

- Expect bumps in the road and be prepared to make adjustments. Successful integration of a new curricular resource takes time, effort, and collaboration. So, as you work with your team to implement new routines and procedures using these carefully chosen materials, be prepared to encounter some challenges that you will have to figure out. And remember, the curriculum alone will never be adequate. Effective teaching and decision-making, responding to the needs of students, and making wise adjustments will ultimately be the determinants of student success.

So, what are those “Must Haves” and “Look Fors”?

The search for the right resources to support your instructional framework requires a deep investment of time and energy, so you want it to be as efficient as possible. To get your team members on the same page and to streamline the review process, you will need a checklist, a rubric, or other evaluation tools (See #1 in the list in the previous section.).

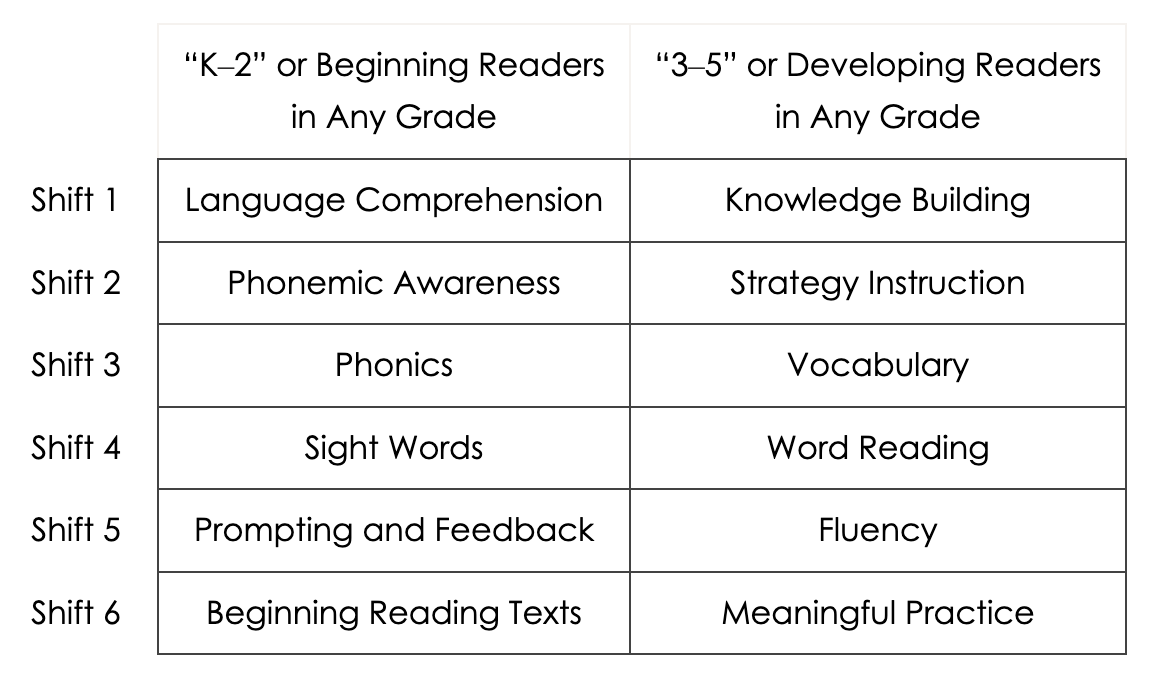

When we wrote the first Shifting the Balance book, our goal was to think about the six essential elements for beginning reading instruction. Eventually, we wrote the second book with Katie Egan Cunningham to do the same thing for teachers in grades 3–5. So, for beginning readers (the first book) and developing readers (the second book), we have condensed reading research down to six essential elements (that’s 12 in all) that should be considered as you are developing a science-aligned literacy framework and selecting strong instructional materials.

As a place to start, you may want to consider the topics represented by each of the shifts in these two books, which are also the shifts we explore in our online classes. We have listed these twelve shifts in the table below so that you can weigh how well various purchased or locally developed curricula will support student learning in these essential areas. As we think about what needs to be included in a resource, we consider the science-aligned routines and instructional moves (or equivalents) in these twelve areas to be our “MUST HAVES.”

Looking for Curriculum Evaluation Tools to Support Your Process?

Below are some links to tools designed to help school teams grapple with the complex work of evaluating and selecting language arts curricula.

- If you’re interested in exploring a knowledge-building curriculum, check out this page on Natalie Wexler’s Knowledge Matters Campaign Website.

- Curious about how Baltimore Public Schools transformed their approach to instructional materials? Check out this insightful read.

- The Reading League offers this Curriculum Evaluation Tool, as well as Guidelines and an Editable Workbook.

- This Explore Reports Tool from EdReports is designed to provide information about the evidence and scientific alignment of curricular materials.

If you want more than a printable tool or an online workbook to help you evaluate your needs, we offer district literacy audits to help leaders identify instructional strengths, opportunities, gaps, and overlaps. These insights are a helpful first step in developing a literacy framework, identifying and reviewing curricular materials, and planning for related professional development. To learn more about our literacy auditing services, and other professional development support, read more here.

References:

Bond, Guy L. (1966). First-Grade Reading Studies: An Overview. Elementary English, 43(5), 464-470.

Readence, John E. (Ed.) & Barone, Diane M. (Ed.). Revisiting the First-Grade Studies. (1997). Reading Research Quarterly, 32(4).