In our last blog, we used a map-reading metaphor to introduce Linnea Ehri’s phases of word learning (1987, 1995, 2002, 2005, 2017). Today we take that conversation a step further by l unpacking a specific (and in many cases beloved) prompt that we’ve relied on to support readers when they get to a word they don’t know: “Look at the picture.”

This familiar prompt is often the backbone of beginning reading instruction in early literacy classrooms. It is so commonly used, in fact, that it is rare to watch a guided reading lesson and not hear it or see children spontaneously use it as a primary strategy for “reading” the words.

In many cases, the prompt is further reinforced with the “Beanie Baby” character, Eagle Eye. Eagle Eye, of course, is a mascot chosen to make remembering to look at the pictures more fun and less abstract. And, of course, making the important things we want young children to remember more concrete, engaging, and memorable is sound pedagogy. The problem, however, was not the tool, although honestly, it may have sometimes been more than a bit of a distraction. The problem was the prompt it represented!

The problem? Turns out, the Eagle Eye prompt– ”Look at the picture”– does not help readers soar. In fact, although used with the best of intentions, Eagle Eye is an example of a strategy that may look successful at the moment but actually weighs readers down, interfering with future flights.

Let us explain.

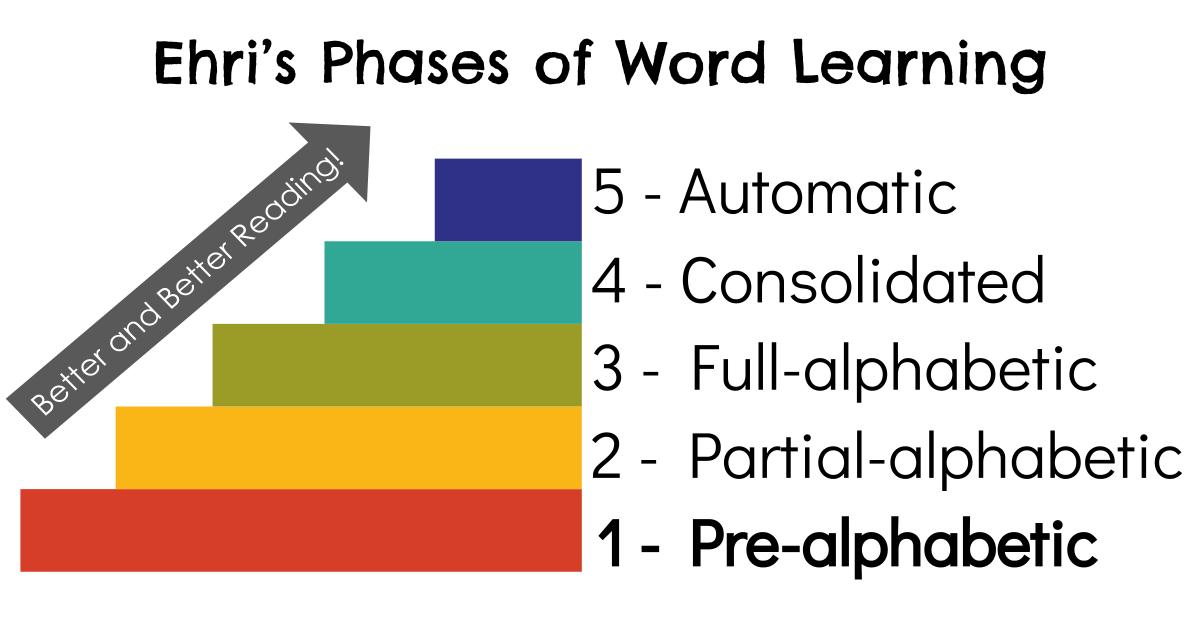

Remember Part 1 in this series, where we introduced Ehri’s phases of word reading? Well, the very first phase of word reading is the pre-alphabetic phase–it’s the phase before children use any information from the alphabetic system. This is where children know almost nothing about how sounds and letters work. They actually use anything but the print on the page.

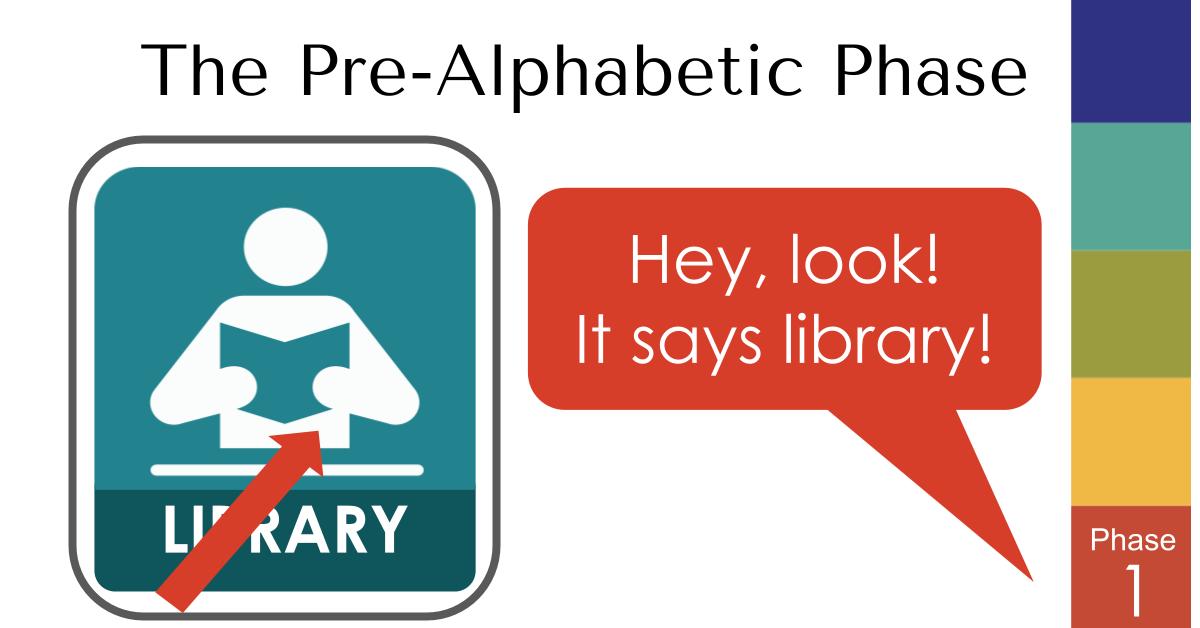

In the pre-alphabetic phase, when they don’t actually know how to read, children rely on the picture landmarks in the text. They read the library sign below by looking at the picture of the person reading and give little or no attention to the word LIBRARY. Of course, the next time they need to find a library and the signs don’t have an icon, what will they do? In terms of learning to actually read, this “reading” has done little for them.

So to say to a reader, “Look at the picture,” is to take them away from the print and actually prompt them to read like a very unskilled and immature reader. It actually communicates, “You can read without using the print.”

In fact, one of the reasons looking at the picture may have become so widespread is because of how it helps us avoid the less beloved prompt, “Sound it out,” and the tedious work that it often requires (more on that later in this series). Again, we do this with the best of intentions. We want to see children have success and “feel like readers.”

Still, this avoidance of the print may mean that children feel like readers and have an easier time in some of their first experiences with text, but feeling like a reader and actually being a reader are two different things!

Perhaps you are wondering, “Yea, but they are immature readers at that point. Shouldn’t we prompt them this way until they learn how the print works?”

Well, the short answer is, no.

The long answer is that to prompt children to use the landmarks (pictures) in the text instead of the print (and the sounds it represents) is to actually teach them a hack for getting to the destination (the word) without actually teaching them how maps (the alphabetic system) works. This prompting delays learning about the alphabetic principle and even habituates inefficient habits that aren’t so easy to break later. They may even need an intervention to break the habit.

What’s more, even though Eagle Eye may seem helpful temporarily when children are working in leveled guided reading texts – most of which, unfortunately, have been written to encourage and even require beginning readers to use the pictures to figure out words – it’s a strategy that will soon clip their wings, making it much harder for them to find their way through text and eventually leave the nest to fly on their own.

And the texts don’t even have to get that much more complex for using the pictures to figure out the words will fall completely apart. In third grade, for example, when they have to read a science text about volcanic gases and the picture on the page is of a mountain, the strategy is of little use. Although picture cues may seem to be a helpful support early on–the usefulness of picture support quickly goes down as text complexity goes up. This inverse relationship leaves students who’ve relied heavily on pictures and avoided the print feeling grounded and confused.

And last but certainly not least, “reading” the word library by looking at the picture on the page does nothing to help them read the word without the picture next time. So this experience with the word has done nothing to actually help them learn about the orthography of the word library so that they can recognize it the next time they encounter it.

Basically, to avoid teaching children how to actually decode a word and instead use a picture to figure it out may be easier for them in that particular moment, but it does little to nothing to support future reading success (more on this in an upcoming post in this series, too).

In the rearview mirror, this seems a bit obvious. We wish that we had understood this sooner.

So – whether using a stuffed animal, a handy bookmark, a poster on the wall, or just our verbal prompts – we need to avoid teaching children to “Look at the picture.” It’s just not a viable or sustainable strategy for reading. At best, this strategy slows progress down; at worst, it leaves children stuck, frustrated, and without the skills they need to move forward.

And if thinking about the downside of a prompt that may be the bedrock of your reading instruction has left you confused, angry, or even regretful, you’re not alone. We’ve been there, too. We encourage you to make space for those feelings. Making substantive change to practice isn’t just intellectual or technical work, and it’s also work of the heart. So take care of your head and your heart as we move through this series together. (We wrote The Six Commitments to help you do just that.)

We hope you’ll stick with us as we continue to use Ehri’s Phases to unpack some prompting mainstays that–despite our earnestness and good intentions- turn out to be less helpful than many of us had believed. Hint: The next stuffed animal friend we will consider says, “Ribet!”

Until next time, we send you off with much love!

❤️ Jan and Kari

P.S. Wondering what to teach instead of picture clues?

You guessed it!

Use a prompt that directs children to use the print, drawing on all they know about sound-spellings. Here are some of our favorites:

- “Sound it out.”

- “Look all the way across the word. Make the sounds.”

- “Keep your eyes on the word. Put the sounds together.”

Then, only after students have used all of the print–sound-by-sound from left to right–to come up with what they think is the word, do we follow up with prompts like, “Did that make sense?” or “Does that sound right?” This keeps decoding as the strategy of first resort, and context and meaning as ways to confirm decoding attempts.

If you want to learn more about this important topic, it is the primary focus of Shift 5 in our book – Shifting the Balance: 6 Ways to Bring the Science of Reading into the Balanced Literacy Classroom – and in our online class.

References

Ehri, Linnea C. 1995. “Phases of Development in Learning to Read Words by Sight.” Journal of Research in Reading Research 18 (2): 116-125.

Ehri, Linnea C. 2005a. “Learning to Read Words: Theory, Findings, and Issues.” Scientific Studies of Reading, 9 (2): 167–188. doi: 10.1207/s1532799xssr0902_4

Ehri, Linnea C. 2005b. “Development of Sight Word Reading: Phases and Findings.” In M. J. Snowling and C. Hume (Eds.), The Science of Reading: A Handbook (pp. 135–154). Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Ehri, Linnea C. 2017. “Orthographic Mapping and Literacy Development Revisited.” In Theories of Reading Development, ed. K. Cain, D. L. Compton, and R. K. Parrila (pp. 169-190). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: John Bejamins, doi: 10.1075/swll.15.08ehr.

Explore the whole blog series:

Showing Young Readers How to Navigate the Phases of Word Reading

Part 1: A Journey Through Ehri’s Phases

Part 2: Why Looking at the Pictures Isn’t as Helpful as We Thought

Part 3: Why Looking at the First Letter of the Word Isn’t Enough

Part 4: Problems With Skipping Words

Part 5: The Downsides of Asking Children to Search for Chunks in Words

Part 6: The Power of Teaching Students to Blend Words

BONUS: The Power of Teaching Readers to Try Alternate Sounds

You are both so inspirational to me. I am taking your summer course and loving every phoneme ;0)

I am a special Ed teacher in a therapeutic day school for students with LD’s. Many students have dyslexia, apraxia, and high language needs. The “6 Shifts”are crucial for my students and our school is a last hope for many readers. The public school system basically failed most of my students-left them feeling broken and a misfit.

I work very hard to build their self-confidence, their trust, and to bring a sense of joy into their literacy block. Your wisdom and teaching sparks my joy so thank you for all you do to inspire us.

Your comment about the class cracked us up! So glad you’re enjoying it!

I appreciate this blog post so much. I was a “beanie baby” teacher all those years ago, and those that didn’t use those used a glove/hand with similar strategies on it. I still get knots in my stomach, knowing I may have hindered those batches of students.

Anyway, along the lines of this post, I thought of something else that teachers may often say. At the beginning of kindergarten, one of the centers/stations we often send kids to during the rotation is the classroom library. Sometimes they will say, “But I can’t read yet, why should I go look at books?” What is the best response for this, do you think?

Mandy,

Thanks for your work in supporting young readers. We can model lots of different ways to interact with books, one of which is using books to further develop and practice oral language with a partner. This can work well with familiar texts and working to retell, but students can also have conversation with partners about what they notice on the pages of the book. We don’t want to limit children from having their hands on all kinds of rich text from the earliest stages, but also want to make sure that is balanced with books in which they can begin to “read the words”.