Text structure is widely accepted as something worth teaching because awareness of a text’s structure can enhance reading comprehension (See References below). There seems to be little dissension on this widely accepted understanding of how our brains can better navigate texts.

Upper elementary classroom walls are often flanked with charts that illustrate and define the five familiar text structures: description, procedural/sequential, compare and contrast, cause and effect, and problem/solution. The logic of this idea is that children can see the cue words that indicate a text’s structure—i.e., first, next, last—as stones they can step on while crossing a river of text.

Beyond the 5 Text Structures

But there’s a lot more to a text’s structure, whether fiction or nonfiction, than these five organizational patterns. Defining text structure narrowly by these five types is a bit like defining music as “the science or art of ordering tones or sounds in succession, in combination, and in timed relationships” or defining marriage as “the state of being united as spouses in a consensual and contractual relationship recognized by law” (Merriam Webster). While these definitions are technically accurate, they certainly don’t capture the depth, emotion, or experience of being moved by a piece of music or of being married.

Pigeon-holing text structure, instructing children to look for cue words, and using those words to identify a text’s particular structure is (unless the text is rather contrived and formulaic) a very limiting approach to considering a text. Even more problematic is the reality that teaching children to narrowly focus on cue words and a few text types actively teaches them to overlook all kinds of other things that make that text cohere.

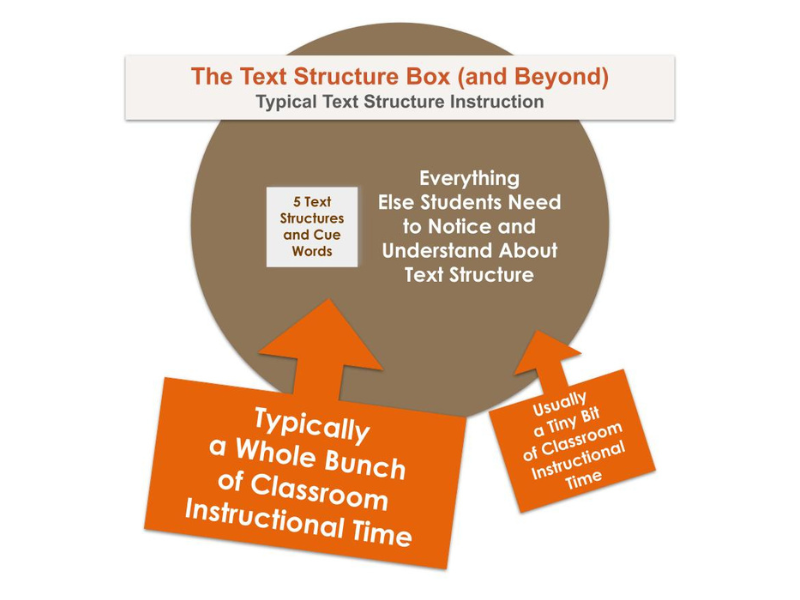

The image below illustrates the common division in classroom instructional time when it comes to teaching text types. Of course, the illustration is metaphorical and anecdotal rather than scientific. But we hope it makes the point that children actually need our instruction about text structure to expand way outside the box of the five familiar patterns.

The overlooked elements of a worthwhile text are often those that make it idiosyncratic, interesting, and even comprehensible. Discovering the many dimensions of a text’s structure out and beyond the box of “the five types” is part of what makes reading enjoyable. Our pattern-seeking brains love to make powerful and deep connections between words, phrases, sentences, paragraphs, sections, and chapters across a text. This is part of how we create and continually revise mental models of the text as we read.

So, what do students need to know about how texts—especially complex texts—are constructed to better understand and enjoy them? Well, while recognizing a text’s structure in the traditional sense (i.e., cause-and-effect, description, etc.) is often a helpful skill, many texts don’t even follow conventional structure rules at all, so exploring how they are built will require thinking outside the traditional text structure box. This fun and challenging work invites students to consider lots of additional structural elements besides those formal structures. Examining how a text is constructed requires us to zoom out to see the whole text and to zoom in on words, phrases, and sentences. It also requires us to keep asking ourselves how all the pieces fit together.

In this post, we go beyond the five common text structures to consider more broadly and more specifically, how different parts of a complex text relate.

So, let’s roll up our sleeves and try a bit of real-world text structure work.

Zooming In: Looking at the Details of Text Structure

Say you are out for a walk, and you pick up a book at a little free library in your neighborhood. You open the small-ish book to a random page about three-fourths through. On the left-hand side of the page, you see the bold heading “Ingredients,” followed by this list.

1 cup of heavy cream

6 eggs

cinnamon

syrup

What comes to mind when you read this list?

What do you notice?

Well, given that the left-hand page is a list (incidentally, not one of the five types of text structure), and the list is made of food items, you might logically conclude that the ingredients list is part of a recipe and likely a dessert. “Perhaps,” you think, “this book is some kind of cookbook.”

Based on these hypotheses, you continue looking at the book. On the right-hand page, opposite the page with the list, is the heading “Preparation.” Ahhh, yes, it is definitely a recipe!

What comes to mind when you read this list?

What do you notice?

Well, given that the left-hand page is a list (incidentally, not one of the five types of text structure), and the list is made of food items, you might logically conclude that the ingredients list is part of a recipe and likely a dessert. “Perhaps,” you think, “this book is some kind of cookbook.”

Based on these hypotheses, you continue looking at the book. On the right-hand page, opposite the page with the list, is the heading “Preparation.” Ahhh, yes, it is definitely a recipe!

You read on. In paragraph format beneath the Preparation heading, the text reads:

Take the eggs, crack them, and separate the whites. Stir the six yolks with the cup of cream. Beat until the mixture becomes light. Pour into a pot that has been greased with lard. The mixture should be no more than an inch thick in the baking pan. Place it on the heat over a very low flame and allow to thicken.

After reading this paragraph, you understand that these are ordered directions for cooking a dish using the ingredients listed on the opposite page. As for the text structure, or paragraph structure in this case (and in many cases), this is undoubtedly a sequential text.

Yes, surprisingly, this paragraph has none of the usual cue words we might teach children to count on to identify a sequence, not a single one! So, how do you know that this is a sequential paragraph?

Whether you know it or not, your brain has already zoomed in to the sentence level. And in doing so, it has likely noticed that the structure of most of the phrases in this paragraph gives clues to the structure of the whole paragraph. All but one phrase is an imperative, or “bossy” phrase, beginning with a verb that gives a command—take, crack, separate, stir, beat, pour, etc. So even without the “Preparation” heading or the familiar, first, second, third, you know this paragraph is giving directions just because of the repeated structure of the sentences.

Furthermore, your background knowledge, vocabulary, and knowledge of language structure likely set you up to make the inferences this text requires of you. And the sum of this paragraph’s inferences is that these are related actions that must be taken sequentially. After all, you can’t exactly separate the eggs before you crack them and can’t pour the mixture until you beat it to a pourable consistency. All these subtleties of the text’s structure keep your brain busy, and without them, the text really wouldn’t be comprehensible.

But that’s not all.

On the word, phrase, and sentence levels, there is still a lot more to understand. For example, the very first word of the paragraph is “Take.” This particular word relies on the upcoming words—the eggs—to communicate an idea. Structurally speaking, your brain knows that the word “Take” will need partners to become meaningful, and your brain immediately begins looking for those companion words in the upcoming text. This relationship between words is called a cataphoric reference. Sometimes, the words that support each other are right next to each other—as in “Take the eggs”—and sometimes they are far apart so that your brain has to suspend understanding for longer.

Simultaneously (practically speaking), you also have to infer that “the eggs” refers specifically to the six eggs from the ingredients list. This type of word connection is called an anaphoric reference, where a word refers to previous information in a text.

In fact, the few sentences in this short paragraph of text are full of cataphoric and anaphoric references, from knowing that the word them in the phrase “crack them” is referring to the eggs, to understanding that the “baking pan” in the fourth sentence was a “pot” in sentence three. If we drew lines between the words connected in this paragraph, there would be so many that we probably wouldn’t be able to see the words at all!

But that’s still not all.

You have to understand this text well enough to translate it into action that results in something edible, hopefully even delicious. So, after you’ve read “Take the eggs,” you have to infer that “take the eggs” means to take them in your hand or pick them up. “Take” doesn’t mean take them from the chickens in the coop or take them from the refrigerator, or take them on an outing in the park. And “crack the eggs” doesn’t just mean put a fine fracture in them and set them back down or to tell them a joke that makes them crack up. No, “crack the eggs” means break them open and dump out their contents.

For you, connecting the individual elements of this paragraph’s structure is probably easy, even obvious. But zooming in on the internal structure of a paragraph requires quite a bit of working memory, background knowledge, vocabulary, and knowledge of language structure—which most of us tend to take for granted.

Zooming Out: Looking at the Big Picture of a Text’s Structure

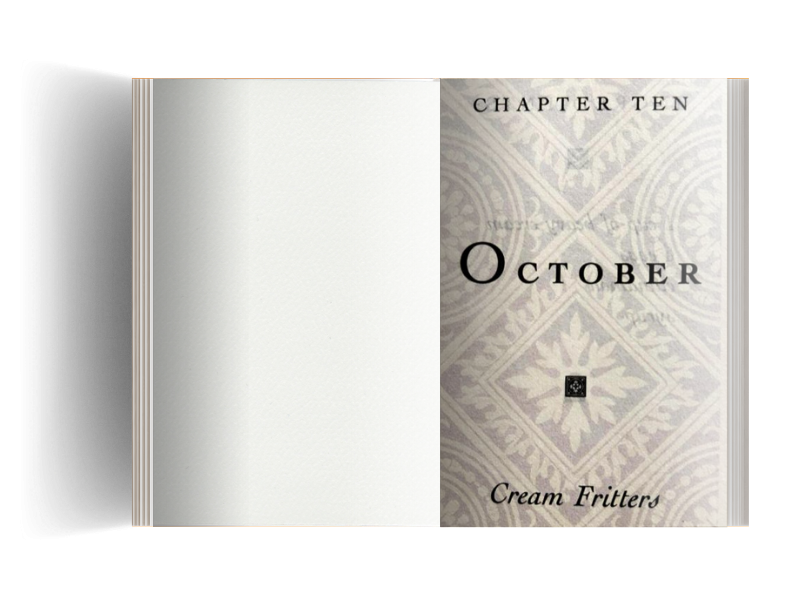

But—even with this clever zooming-in that you’ve done—you still have to actually comprehend the text as a whole. So, back to you, leaning against the little free library with this unusual book (complex text) in your grasp. Curious, you flip backward a page because you still aren’t even sure what dish this recipe is describing. You see this:

Clearly, this is the title page for a chapter. And you quickly infer that the recipe you’ve been scrutinizing is for cream fritters. Apparently, you, the reader, are supposed to make these fritters in October.

“Ahhh,” your brain thinks to itself, “this is a book that goes through the year and presents recipes (or just one recipe?) for each month.” You flip through the twelve chapters and confirm your hunch; the other chapters do, in fact, present single recipes, such as ox-tail soup in July and chiles in walnut sauce in December. You also notice that the recipes have a Latin thread and that most of the dishes are unfamiliar to you.

Things are starting to make sense. From a bird’s-eye-view, the text structure of the whole book, or the book’s superstructure, is twelve chapters that roll out chronologically across the months of the year, with each highlighting a single recipe (and its sequential directions) that is, perhaps, a hallmark for that month. It seems to be a sequence within a sequence. Hmmm.

Zooming In: Looking at the Details of a Text’s Structure (Again)

You flip back to the recipe that you originally started with, the one for cream fritters. You reread the opening procedural paragraph with its cracked eggs and low flame and continue into the next paragraph:

Tita was preparing these fritters at the specific request of Gertrudis, they were her favorite dessert. It had been a long time since she had had them, and she wanted to make them before leaving the ranch the next day.

Wait a minute! A structural twist! Your brain now has to rethink some things because, even though this is a book full of ingredient lists and recipe procedures, these two sentences, albeit connected, are doing something completely different. These sentences are sequential in a different way—they are narrative, told like a story about the circumstances surrounding a particular time when someone made cream fritters for someone else.

Your brain has seen cookbooks with little stories in them before. Maybe the author is trying to personalize the recipes and bring them to life by describing a time when they made these fritters for Gertrudis, whoever that is. You flip to the cover to find that the author’s name is actually Laura, not Tita or Gertrudis.

It is then you realize that the text is a novel, not a cookbook. You’ve figured out something more, something big that makes everything else make sense, and your brain really likes that.

The book is called Like Water for Chocolate (Doubleday, 1992), and while cooking and recipes propel the storyline across the year structure that holds it together, it is actually a story.

Putting It All Together: A Short List of the Big Ideas About Text Structure

In many classrooms the organizational “big five” text structures have been emphasized to the exclusion of other important elements of text structure. Although the text types and corresponding signal words that children are often taught can be helpful, they are only a piece of what we need to consider when we teach about text structure. They certainly aren’t foolproof paths to identifying a particular text’s structure.

And, even more importantly, tagging a text structure with a specific label does little to support the ultimate goal of reading—understanding the important ideas the author is offering.

Being able to name and elaborate on all the ways Like Water for Chocolate is organized is not—in and of itself—all that important when it comes to understanding the text. What is important, as a reader, is being able to leverage the structural details of a text in ways that facilitate and enhance our meaning-making path.

So, how do we help children tune in to all of the subtleties of text structure—at the word, phrase, paragraph, section, chapter, and superstructure level? The best way we know is through interactive experiences with texts that stretch (and even break) the text structure rules, pushing students’ thinking about text structure out of the box.

During read-aloud, shared reading, and even small group experiences with interesting texts, we can invite curiosity and thinking aloud about how an author has organized a text so the reader can understand it—with patterns, coherence, comprehensibility, suspense, surprise, and more.

References

Bogaerds-Hazenberg, S.T.M., Evers-Vermeul, J., & van den Bergh, H. (2020). “A meta-analysis on the effects of text structure instruction on reading comprehension in the upper elementary grades.” Reading Research Quarterly, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.311.

Esquivel, L. (1992). Like water for chocolate: A novel in monthly installments with recipes, romances, and home remedies (C. Christensen, Trans.). Doubleday.

Hebert, M., Bohaty, J.J., Nelson, J.R., & Brown, J. (2016). The effects of text structure instruction on expository reading comprehension: A meta-analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 108(5), 609–629.

Meyer, B. J. F. (1975). The organization of prose and its effects on memory. North-Holland Publishing Company.

Meyer, B.J.F., & Ray, M.N. (2011). Structure strategy interventions: Increasing reading comprehension of expository text. International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education, 4(1), 127-152.

Pyle, N., Vasquez, A., Lignugaris/Kraft, B., Gillam, S., Reutzel, D., Olszewski, A., . . . Pyle, D. (2017). “Effects of expository text structure interventions on comprehension: A meta-analysis.” Reading Research Quarterly, 52(4), 469–501.

Shanahan, T. (2020, February 8). “Does text structure instruction improve reading comprehension?” *Shanahan on Literacy*. https://www.shanahanonliteracy.com/blog/does-text-structure-instruction-improve-reading-comprehension.

-

Jan Burkins and Kari Yates are authors, speakers, and consultants, who are dedicated to helping teachers around the world translate reading science into simple instructional moves that help teachers make learning to read easier for their students while still centering meaning-making, engagement, and joy.

Recent Posts

This post is needed and brilliant! It reminds me of the same issue of teaching key words to help solve word problems in math. How are we tapping into deeper thinking when offering such limited ideas? Noticing and wondering about text structures during read alouds is so powerful. Children can try out similar structures from mentor authors in their own writing. Thanks for this awesome post,

Thank you, Lisa! 💡 You make such a great connection to math—just as relying on key words in word problems can be limiting, oversimplifying text structures can prevent students from truly understanding how ideas connect. Encouraging students to notice and wonder about text structures during read-alouds is such a powerful way to build deep comprehension and writing skills. We love the idea of students experimenting with these structures in their own writing—what a meaningful way to bridge reading and writing! Thanks for sharing your insights and for your kind words. Keep us posted on how this work unfolds in your classroom! ✨📖✍️

Very helpful, elegant descriptions of thinking about texts, paragraphs sentences, phrases and words. I want to read and talk about this more!

Thank you, Sasha! 😊 We’re so glad you found it helpful. The way we think about texts—from big ideas to the smallest details—can truly transform reading instruction.

Text structures!!