Vocabulary is a hot topic in the world of literacy right now. More and more educators wonder, “What is effective vocabulary instruction?”

Effective Vocabulary Instruction

And we know there are lots of opinions and options about the best way to teach vocabulary.

So . . .

Should we teach vocabulary incidentally through spoken language across the learning day, extending what children say and teaching them routines for engaging in conversations about the things they are learning?

OR . . .

Should we teach vocabulary on the run and in context as we read aloud and support shared reading? Seems like this instruction is really authentic, which matters to us.

OR . . .

Should we provide formal vocabulary lessons on individual words that we explain and illustrate explicitly? There is certainly pressure to teach pretty much everything more explicitly these days, and we don’t want to overlook something that will help our students, even if it’s not our first or favorite choice.

OR . . .

Should we give children lots of opportunities to read independently and practice noticing and collecting new words on their own, leveraging self-teaching via incidental exposure and use of context clues? It seems that if we want children to be readers, we need to give them time to practice, so independent reading is a win-win.

Well, the short answer to which of these four instructional options is the best way to teach vocabulary is—ALL OF THEM!

What do we know about the most effective strategies for vocabulary instruction?

A large body of research (NICHHD 2000 reading panel citation) confirms that, YES, each one of these instructional strategies for teaching vocabulary offers an important pathway for you to really deepen students’ vocabulary knowledge. But it’s not a matter of choosing one. It’s a matter of choosing them all.

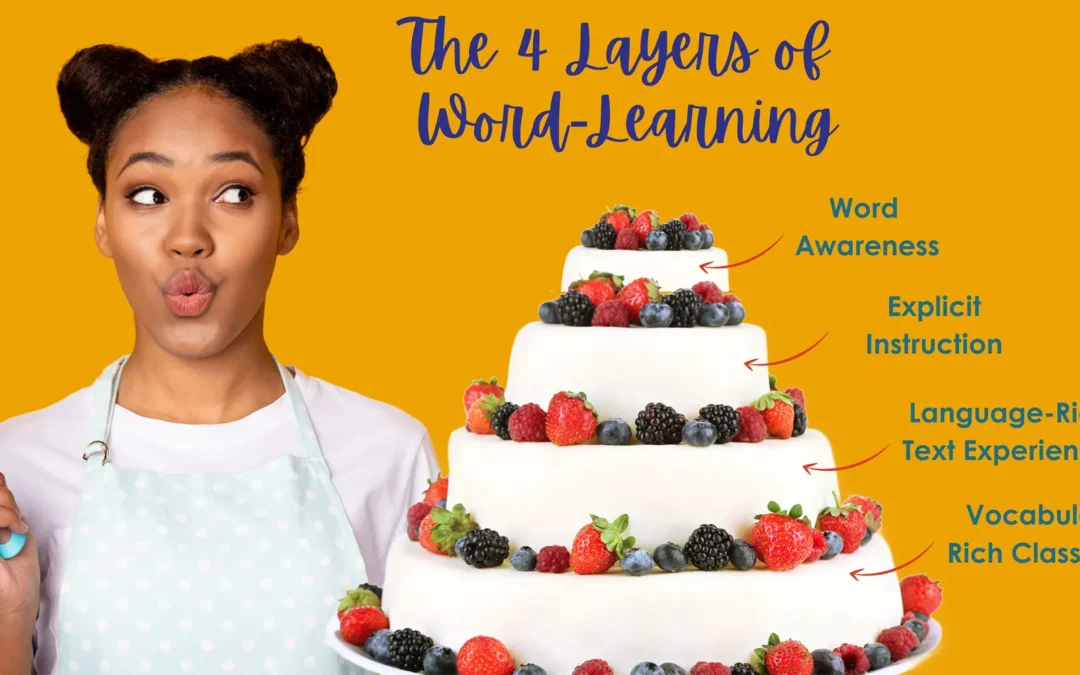

Students acquire the most vocabulary and understand new words better in classrooms with a teacher who uses ALL four of these instructional approaches. We think of these four strategies a bit like layers of a cake.

Sound like a lot? Don’t panic!

The four layers of sound, brain-friendly vocabulary instruction are complementary. (And we think that four layers of cake are better than one or two layers any day—after all, that means you get four times the frosting!)

Chances are, you already have some of these layers in place. And once you pull in any that you haven’t yet included—while maybe also sweetening up the existing layers—you’ll likely find that your students have a real sweet tooth for learning words!

Layering Instructional Strategies for Vocabulary

Of course, layered vocabulary instruction takes some real thought and planning, just as putting together a four-layer cake does.

So, we offer a few questions to help you reflect on each layer of your vocabulary instruction:

Layer 1: VOCABULARY RICH CLASSROOM—fostering a learning environment that floods students with rich vocabulary all day long

- Do your students encounter interesting words incidentally throughout the day?

- Are you intentionally elevating your own vocabulary across the day rather than watering words down for students?

- Do you have structures for students to turn-and-talk with each other about what they are learning? And do you use these structures throughout the day, every day?

- How vocabulary-rich is your environment?

- How might you improve Layer 1?

Layer 2: LANGUAGE-RICH TEXT EXPERIENCES—consistently selecting texts with rich vocabulary for shared text experiences (such as read-aloud and shared reading) and being intentional about how you engage students with the new words

- Do you employ both read-aloud and shared reading in your classroom?

- Do you teach the meanings of words students need to know to understand the texts during these interactive text experiences?

- If so, how do you narrow down the words, and which do you pre-teach before the lesson, and which do you teach on the run during the lesson?

- Do you find that students use these words later in their speech and/or writing?

- How vocabulary-rich are the shared text experiences in your classroom?

- How could you improve Layer 2?

Layer 3: EXPLICIT VOCABULARY INSTRUCTION—choosing a small collection of new vocabulary words to teach explicitly

- Does your literacy block routinely include time that is dedicated specifically to vocabulary work?

- What does this explicit vocabulary instruction look like?

- How do you decide on which words to teach explicitly?

- Do your vocabulary lessons include all four parts of explicit vocabulary instruction that make learning words easier for the brain?

- Are students actively engaged in the instruction? Why or why not?

- Do you find that students use these words later in their conversation and/or writing?

- How confident are you in your explicit vocabulary instruction?

- How could you improve Layer 3?

Layer 4: WORD AWARENESS—cultivating word awareness in your students through jokes, puns, and wordplay and encouraging a general love of words

- Are your children excited about finding and using new words?

- Do you intentionally embed wordplay (puns, jokes, riddles) into the classroom culture?

- Do students notice new words during their independent reading and have opportunities to share these words with you and other students?

- Do you encourage students to experiment with words?

- Do you have an interactive vocabulary word wall or other tools for highlighting new and important words?

- Do students apply context (clues outside the word) and morphology (clues inside the word) to figure out a word’s meaning independently?

- Do students have a notebook or other tools to collect the words that interest them?

- How word-aware are your students?

- How could you improve Layer 4?

If you want to dig into a larger slice of this vocabulary cake and think about these layers more deeply, you may want to take a look at Shift 3 (Chapter 3) in Shifting the Balance: Bringing the Science of Reading into the Upper Elementary Classroom (Cunningham, Burkins, & Yates 2023) or our online class by the same name. And don’t let the book title fool you; vocabulary learning is for all grades! Your students are hungry for a generous slice of vocabulary learning! A layered approach will set them up to learn more new words faster.

References

Duke, Nell, and Kelly Cartwright. 2021. “The Science of Reading Progresses:

Communicating Advances Beyond the Simple View of Reading. Reading

Research Quarterly, 56(S1): S25-S44.

Gough, Philip B., and William E. Tunmer. 1986. “Decoding, Reading, and

Reading Disability.” Remedial and Special Education 7(1): 6—10. doi:

10.1177/074193258600700104

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. 2000. Report of the

National Reading Panel. Teaching Children to Read: An Evidence-based

Assessment of the Scientific Research Literature on Reading and its

Implications for Reading Instruction: Reports of the Subgroups (NIH

Publication No. 004754). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Reutzel, D. Ray and Robert Cooter. 2015. Teaching Children to Read: The

Teacher Makes the Difference. New York, NY: Pearson.

-

Jan Burkins and Kari Yates are authors, speakers, and consultants, who are dedicated to helping teachers around the world translate reading science into simple instructional moves that help teachers make learning to read easier for their students while still centering meaning-making, engagement, and joy.

Recent Posts