Decoding practice is a big deal, but . . .

Everywhere we go these days, teachers are working hard to provide more explicit and systematic phonics and word study instruction.

These lessons focus on the word-reading side of the learning to read equation. So, it only makes sense that they revolve around words—lots of words—to provide practice with a specific sound spelling or skill.

In fact, if you’re looking for additional words to support specific skills, we’ve made some bundles of free word lists for many of the basic spelling patterns that are commonly taught. If you’d like to check those lists out, you can find them below.

The Importance of Bringing Meaning into Blending Practice

Regardless of where the words come from, we know that you want your phonics lessons to go far beyond word lists to include regular opportunities to learn the meanings of new words as well as read and write words in context.

Yet, as we visit schools and have the opportunity to spend time in whole-group, small-group, and intervention settings, we see an increasing and worrisome trend within phonics and word study instruction—the lessons are too often almost completely devoid of connections to the meaning behind the words. And often, these lessons with limited focus on comprehension also take up the lion’s share of the literacy block.

You’ve probably heard the tired adage that claims children “Learn to read in primary grades and then read to learn in the intermediate grades.” It’s widespread these days and often implied when it isn’t overtly spoken. But, as it turns out, this separation between decoding and comprehension is a really unhelpful way to think about the reading process.

Students need to think, learn, and make meaning from the very beginning and always . . . every single time they read. Otherwise, they are only decoding (not reading). Decoding is an important skill, but it is limited by language comprehension when it comes to actually READING!

Being Cautious of Overcorrection

Instruction that involves students working really hard to decode words, find words, and write words that fit a particular spelling pattern, while giving little or no attention to thinking about what those words mean is a perfect example of overcorrection in the direction of foundational skills instruction. It is as if we have discovered that we have scurvy and have decided to eat mostly oranges. Eating oranges may help with scurvy, but a diet of mostly oranges will also cause other serious health problems.

In the classroom, overcorrecting towards phonics instruction that has students working really hard to decode words, find words, and write words that fit a particular spelling pattern, while giving little or no attention to what those words mean, not only means we’re missing valuable opportunities to beef up student vocabulary and comprehension, but we are also inadvertently teaching students that sometimes they can read without paying attention to meaning.

The Alternative: Bringing Meaning into Blending Lines and Word Lists

Fortunately, we can make phonics practice more meaning-full, and we can make sure that we aren’t supplanting language comprehension with our efforts to teach automaticity with the code. Since language development is largely a pay-it-forward system (until decoding catches up with language around middle school), the language comprehension we don’t nurture in one grade can become the reading comprehension gap in the next.

So, are you wondering how you can make your phonics instruction even more meaning-full? Well, we have some ideas.

Ways to Make Your Decoding Practices Work More Meaning-Full

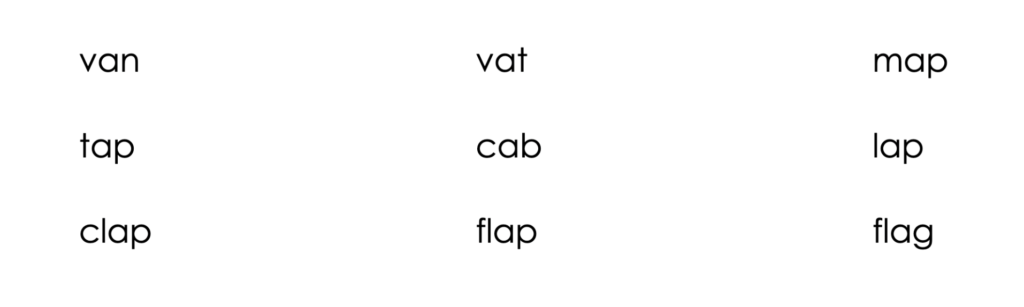

For the sake of demonstration, let’s imagine a group of kindergarten students working on mastering reading and writing CVC words containing the short a sound. Their phonics lesson includes practice blending the following words:

One option would be to move through the entire list, focusing only on decoding the sound-spellings and blending together the sounds to arrive at the word. Your feedback would focus squarely and solely on the correct pronunciation of the words. In other words (pun intended), word reading would be taught separately from meaning-making.

But it is not difficult to embed some meaning work into decoding practice, even when the practice is with words in isolation.

Take another look at the list of words above. What if you were to focus on the meanings of even a couple of words—words that might not be as familiar to some students, especially emerging bilinguals or students who come from homes that are language-rich but not with the language of school? The good news is that a commitment to “drip” meaning-making into every encounter with a word list won’t compromise the integrity of the lesson’s decoding practice. In fact, meaning actually helps the brain to learn words! How about that!

Notice that we aren’t suggesting elaborate vocabulary lessons in the list of ideas below. These are just brief moments of acknowledgment that words have meanings—some even have many meanings—and it’s important (and even fun!) to think about what words mean as we read. That’s why we are learning to decode in the first place!

So, are you wondering how you can make your phonics instruction even more meaning-full? Well, we have some ideas.

10 EASY Ways to Embed More Meaning Into Decoding Instruction

1. Make them visual.

Point to a picture or an object (or even demonstrate): “Fan can be an object, like on our /f/ picture card, or an action, like what I do with a piece of paper when I’m hot.”

2. Provide a simple definition:

“Vat. A vat is a really big pot or bucket used to hold large amounts of liquid.”

3. Offer a synonym.

“Lad: ‘Lad’ is another word for ‘boy,’ similar to how ‘kid’ can mean ‘child.'”

4. Make a connection:

“Ram. Hey, there was a ram in a story we read last week.”

5. Provide a context clue.

“Gap. There’s a gap in the fence big enough for a rabbit to fit through. What do you think gap means? Turn and tell your partner.”

6. Ask students to help define the word. (This is especially useful with multiple-meaning words.)

“Lap! This is a word with lots of different meanings. Who thinks they know a meaning of the word lap?”

Student A: “You can sit on your mom’s lap.”

Student B: “It’s something like the cat does with its milk.”

Student C: “It’s what Mr. Gym calls it when we run all around the

circle outside.”

7. Let students choose a word to define.

“Reread the list of words to yourself. Choose one word to define for your partner. Write the word on your board, say the word, and tell your partner what it means. See if your partner wants to add to your definition. Then switch.”

8. Prompt students to construct sentences orally.

“Reread the list of words, and choose 1-3 words to use in an interesting sentence. Share with a partner and see if they can add to your sentence. Then switch roles.”

9. Ask students to construct written sentences.

“Using one or more words from the list, write a sentence using all that you know about conventions and spelling patterns.”

10. Provide a meaning-related clue for students to solve.

“I’m thinking of a word that means a big pot or pan. Which word is it? Yes, it’s vat. Now, I’m going to cover the word while you write the word, listening carefully for each sound. When you and your partner have both written the word, check each other’s spelling. Partner A tells what the word means. Partner B uses the word in a sentence.”

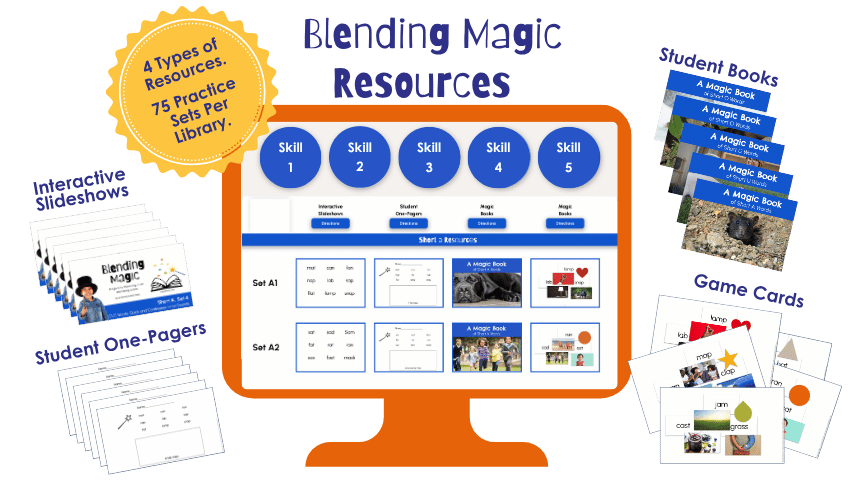

Blending Magic: Magically Meaningful Blending Lines

You can also use Blending Magic, our new set of resources for teaching decoding and spelling closed syllable words (CVC+) in ways that connect to meaning. These resources (a variation on Wiley Blevins’s Blending Lines) teach children to connect, confirm, and/or demonstrate the meaning of the words on a decodable list.

In fact, it is easy to use Blending Magic to integrate any of the ten ideas on the list above. In this routine, the words in a blending line appear one at a time, creating a cumulative list. After children have blended each word, you advance the slide to magically reveal a picture that illustrates the meaning of the word. For example, after children read and say vat, a picture of a vat is revealed. Children can use the image to confirm the meaning of a familiar word or learn a bit about an unfamiliar one. After each picture, the blending line appears again with another word added, and the process repeats.

And, this meaning-full word work isn’t just for beginning decoders. Consider a syllabication lesson where older students work to decode the words construct, submit, contrast, and mishap. The ten ideas on the list above can be adapted for upper-grade word work as well.

This video demonstrates how Blending Magic: Magically Meaningful Blending Lines works.

Phonics Instruction as “The” Problem

“But, wait!” you may be saying, “I thought the big idea was that kids needed more phonics instruction.”

Yes, students do need more phonics instruction that is explicit, systematic, and cumulative. But not at the expense or exclusion of meaning-making. And there is a real risk here. If we overcorrect towards phonics instruction, if we leave kids with the idea that “learning the rules” and “sounding out the words” is what reading is all about, then we’ll end up with kids who can decode well, but who still plateau as readers because they won’t be equipped with the vocabulary and comprehension tools they need. This will potentially lead to people questioning if phonics instruction is really important after all. And it is.

Don’t get us wrong. We’re not suggesting that you abandon word lists and decodable readers. We’re not saying you shouldn’t use isolated lists of words or otherwise provide lots of decoding practice with each new phonics concept you teach.

We’re simply saying not to do all of that decoding work without supporting meaning-making in every “phonics” lesson, too.

Are you wondering how you can ensure that students’ encounters with decodable texts are infused with meaningful opportunities to think, talk, and write about the text? You may want to check out this post, Decodable Texts: What Else to Look for—The Meaning, which is part of our six-part series on decodable texts.

-

Jan Burkins and Kari Yates are authors, speakers, and consultants, who are dedicated to helping teachers around the world translate reading science into simple instructional moves that help teachers make learning to read easier for their students while still centering meaning-making, engagement, and joy.

Recent Posts

Where can I get more cvc slides for the other vowel sounds that are meaning-ful!?

We hope by early June we’ll have the short vowels ready to go! If you’re on your newsletter you’ll get notification.

Where can I get blending line slides for the other cvc vowels words?

We’re currently working on all of the other short vowels and will follow with long vowels. We hope by early June we’ll have the short vowels ready to go! If you’re on your newsletter you’ll get notification.

Great post. Thank you!

It raises something that has been in the back of my mind lately. I have been questioning the value of using nonsense words (as many phonics programs do) in instruction or assessment because you are detaching meaning. Often as they are decoding they can start to hear a word they know and it helps them get it. Why take that away?

It doesn’t seem like a good instructional practice because you are teaching them to read without meaning, and it doesn’t seem like an accurate assessment because you are taking away some of their important tools they can use to read!

Aaron.

We’ve grappled with this same worry about nonsense words for a long while.

Lately, we’ve made a bit of a shift. Yes, we want to teach children to ask themselves, “Does that sound like a word I know?” after making their best decoding attempt. This is sometimes referred to as relying on “set for variability”. Reading is about meaning making. But once children have gotten their feet under them with single syllable words, they will need to quickly make the move to reading more and more words with multiple syllables, and when they happens, they will begin to encounter lots of syllables that don’t make sense. Therefore, a shift we’ve made is to supporting some practice with chucks that aren’t actual words. A subtle shift we’ve made is from calling them “nonsense words” to calling them “nonsense syllables”. We don’t advocate for high volume practice with nonsense syllables, but sprinkled in with clear attention drawn to the fact they they aren’t real words can benefit for some students, not just at the single-syllable level, but more importantly with bigger words.

Thanks for your deep thinking about the relationship between decoding and meaning-making!