In Chapter 1 of Shifting the Balance, we untangle a widespread misunderstanding about reading comprehension. It is “Misunderstanding 4” in the chapter that is about language comprehension.

Misunderstanding 4 goes like this,

“Successful comprehension in beginning reading texts means that reading comprehension is on track.”

Unfortunately, too many of us have worked with too many children who seem to comprehend well in those earliest levels of a benchmark assessment, but then seem to plateau in their comprehension as texts increase in complexity.

In reading lots of research as we wrote Shifting the Balance, we came to understand that, because reading is turning written language back into spoken language so that the brain can “hear” it, if a reader doesn’t have enough understanding of the language of a text, then they won’t be able to comprehend it, even if they can decode it (Gough & Tunmer, 1986).

That’s just what has happened with Letitia, a student at the end of second grade who had seemed to be on track (pun intended!) in the early grades, but who has, over the last months, slipped noticeably in comprehension.

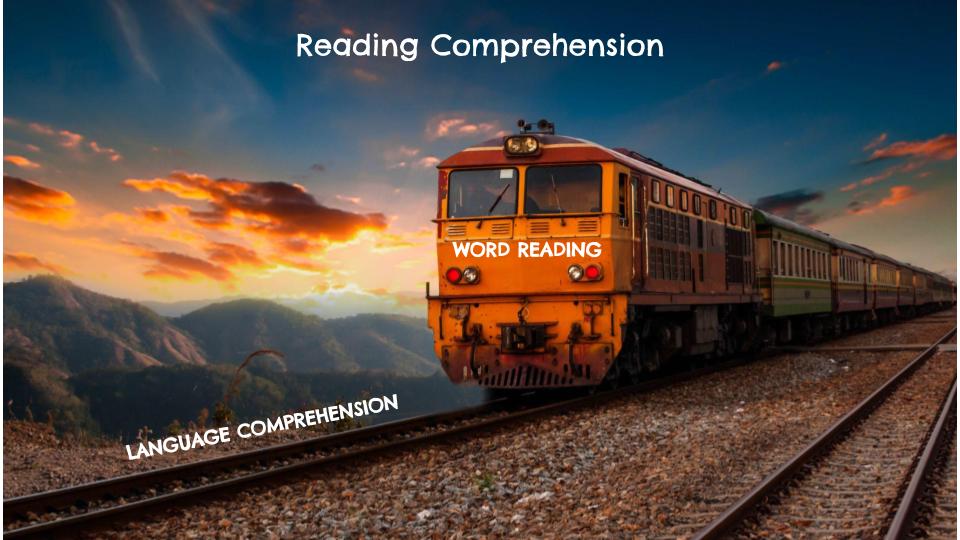

You see, spoken language is the track that the word reading train runs on. And, just as is true with a train, this track has to be laid in advance of the train’s arrival. So, all the language tracks that we lay in preschool and kindergarten become the rails that the word recognition train runs on in first grade and beyond. And so on.

Without the track, of course, you just have a train that can’t go anywhere–or word reading without comprehension. Of course, having a language track without a train, or access to the alphabetic code, doesn’t really take you anywhere either.

But Letitia’s train has run out of track.

With Letitia, and so many other students like her, there were warning signs in the early grades. But these signs were missed because Letitia could always answer comprehension questions about the little texts with controlled vocabulary that she was reading so well.

But then the texts began to gain steam in terms of vocabulary and sentence structure. While Letitia had learned to navigate the decoding demands of texts, her decoding began to outpace her language. So, she was “reading” texts that she didn’t understand. There just wasn’t enough track to keep reading comprehension in motion.

More and more schools are looking closely at systematic, explicit phonics and phonemic awareness instruction, taught with an intention towards mastery rather than coverage (the work of getting the foundational skills train built). This is important work!

But, it is easy to overlook the fact that the train will quickly run out of track if there is not also an intentional focus on building vocabulary, a strong command of oral language structures, and rich background knowledge. In other words, we also need to invest intentional effort in laying the language tracks that word reading runs on.

Comprehension, the ultimate goal of reading, can’t be reached without both the train and the tracks!

We recommend you check out this video from Linda Farrell at Reading Rockets if you want to learn more about the critical interplay between the train (word reading) and the tracks (language comprehension) on the path to reading comprehension.

Gough, Philip B. and William E. Tunmer. 1986. “Decoding, Reading, and Reading Disability.” Remedial and Special Education 7(1): 6–10. doi: 10.1177/074193258600700104

Thank you for these emails! I loved your book! The video was great in describing a decoding vs. comprehension problem that a child might be exhibiting. I appreciate the emphasis you place on comprehension- my school has put great emphasis on decoding this year, and I miss the time I used to spend reading stories, discussing vocabulary, and comparing stories with similar themes…TALKING! I hope to see a more balanced goal for next year.